What won’t Stine say?

-The chicken, though adequately cooked, is sadly under-seasoned. Is there any lasagna, instead? I don’t sanction miniature corncobs.

-Not a bad speech, but let’s try to lose the accent, Mr. Mandela.

-In the land of the blind, the one-eyed man is king, right, Mr. Bocelli?

-Speak up, Mr. Hawking!—Carve your words and spit them out, like me when I shout this command!

-Hats off in the classroom, your Holiness.

-Mr. Devito, stand and deliver! Stand and—oh… Well, then: stand on a chair.

-The short hair doesn’t really favor you, Ms. Degenerous. Something softer, more feminine, perhaps.

-I would have thought you could have turned out a larger audience for our turtleneck reading of Murder in the Cathedral here at the First Baptist Church of Harpswell, Maine.

Something like that last one most likely got said on a Princemere Readers trip into the depths of the Bert-and-I State.

When won’t Stine begin a prayer on just such a trip?

Me: Hi, I’m Mark Stevick from Lancaster—

Stine: FOR THESE GIFTS, AND ALL THY MUNIFICENCE—for these seven residents of the hamlet of Harpswell, Maine, who will host and feed our twelve Princemere Readers—and their servant leader in a separate home because sharing a bed is unseemly in my considerable book… Lord, we thank you—♫ PRAISE GOD FROM—am I the only one spontaneously pray-singing?—♫ BLESSINGS FLOW—next song-prayer: ♫ THE LORD IS MY LIFE, AND—I can’t hear the women—♫ SALVATION!—have you got any more of those cupcakes, I’m a diabetic, but I could use cupcakes, diabetes, lots of jimmies, find my insulin bag, with frosting, if you’d be so kind… No? We’re out of diabetes-cakes? More’s the pity. That’s an expression that means “too bad.” You lobstermen don’t “readie muchie” do you? It’s all right—that’s why we’ve come to your small wooden church with our 3-hour rendition of The Scarlet Pimpernel. No need to feel embarrassed. There was a time in my life when I couldn’t read—AUSTIN?—are we saving some crabcakes for others? Fine.

[continuing] Breakfast tomorrow at half five—that’s 5:30 for you “Mainuhs”—and I know you’re already up then, trimming the mizzenmast, as I myself also constantly am—for the Men’s Matins Meal, or the Clerical Collar Choir practice—♫ WHOM THEN SHALL I FEAR?—or Racquetball for the Recovering—mm?—what’s that? No: I don’t drink coffee, especially not in Harpswell, Maine, ho-ho! I’ll have some tea if it’s English Breakfast, with milk first, not cream, otherwise just sea water in a small conch, I’m not hard to please. No, it’s “conk” actually, not “conch”—thank you very much, you’ve been malapropping it for centuries. If it’s worth correcting, it’s worth correcting loudly. Why compound ignorance with inaudibility?

__

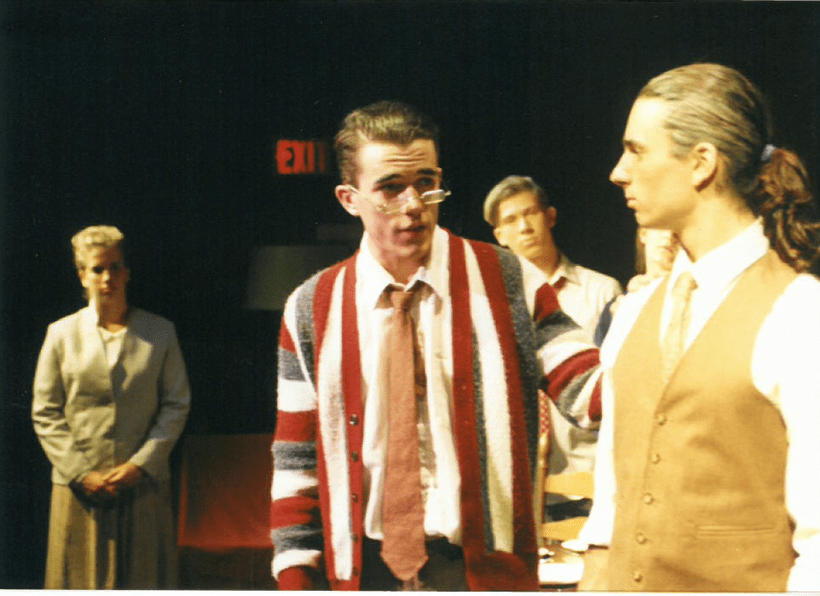

Here at this retirement dinner, I hear you asking: How many such Stineian sayings have occurred on similar Princemere trips? 525 thousand 600 vignettes—no; let me do some accounting: since 1976 when PWS founded the Princemere Readers, two dozen productions have been uttered by a hundred-and-a-half voices for an audience in toto pushing 20k—in nearly half our states (22), and eight countries—thrice in England, (nearly) twice in Kenya, plus Korea, the Philippines, China and Japan.

Begun with a $500 budget, which had increased to $900 when all was read and done in 1999, Princemere was a blue chip investment, certainly. With a few hats and a good script, the Princemeres could perform in slippy black stockingfeet anywhere; and the scene, in the audience’s mind, could look like the Mississippi, or Hell, or Hester’s scaffold in the Puritan marketplace. And because Stine & Co had brought these settings & stories to their front stoops, a goodly number of high school seniors signed on for a Wenham address—and then paid their 6 or 12 or 21 thousand dollars a year for four-or-more years to its only-and-frugal college.

Princemere paid dividends for the Troupe, too. We were, most of us, sow’s ears, being measured and stretched against great literature: the hypotaxis of Hawthorne, and the figures of C.S. Lewis, the phonemes of Dylan Thomas, and Mark Twain’s metallic twang. We were buffeted by the texts, and by the tyrant director, too. What did he teach us but how to mark with our voice and breath, as he did, every flick of punctuation, every emotive vowel, every, every minute?

And, watching him, we learned, too, in talk-backs after the shows, that one may engage an entire room with bluster and finesse, teasing its members into a different kind of play, a tautened alertness, a finely suspended joy. He was at his best, burned cleanest, I think, in those give-and-take afterglows.

And he, he himself, the Stine carved the roast beast—no, he himself adapted all but one of those two dozen productions. Is it too much to say that those 23 publications (for the first public performance of a script is, in the writs of copyright law, a publication)—too much to say that they mattered more to kingdom and college than the several squat volumes on minor Victorian poets that might have borne his name on their infrequently-handled spines? It’s not too much to say that. (Though it was wordy, I lost my grip on the sentence.) Those 300 productions, 300 play-full, literary interludes, were his scholarship, and his reasonable service.

In 1979, Peter was given the Faculty Award by the student body for, among other things, his work with Princemere. In 1999, after missing two consecutive spring tours with foot sores and sickness, he retired from his adapting-of-lit and his troupe-of-readers. I know he would love for the shows to go on; and he had hoped that I could take up the van keys, but, alas, I couldn’t manage it all; maybe if I’d been married, with 4 kids and a pastorate to boot, I’d have had the time.

How valuable, for me, Patrick Gray, Carol Smith Austin and her man Philip, for Dawn Jenks Sarrouf, and Mark Frederick and Jennifer Hevelone Harper to have started out with Princemere; a troupe founded to “make great literature the handmaiden of the gospel of Jesus Christ.” Thanks to Stine I feel like I wrote The Great Divorce and The Scarlet Letter—books I quote often, and impressively, in my classes. Which returns me to my theme. What won’t Stine say. With the slightest of provokings, Stine will deliver a brief, hortatory essay on the value of such literature—and of the amiable word, the vigorous sentence, the paragraph “in the trim.” What he says will be imageful, figurative; it will sound like he’s wholly quoting when, in fact, he isn’t, though he will sample from Heaney or Churchill or Achebe to fine effect. It will be vintage Stine, and it will tingle you under the scalp to hear it, so that you’ll think, If only I could say that the next time I’m called on. As if.

What else will Stine say? Given the merest flash of an opening he will remonstrate with us not to abandon the teaching of public speaking at Gordon. “I speak for the trees, my wooden pupils, for the trees have no tongues.” And O, he is agonizingly right. Should you ever require penance, yours shall be to attend a senior breakfast and hear near-grads speaking cudgels when blades are required.

And this else will Stine say: “Here’s $150 for your Chemistry text; here’s $200 for the student emergency fund; here’s $500 to help get Anne aboard the London theatre trip—I know she can’t afford it, and I have some money from Betsy; but I don’t want anyone to know”—to which one says, “OK. No one will know.” Until your retirement dinner.

All those things will Stine say, along with lots of lively expressions that one hears, as a freshman from Lancaster, PA, for the first time, attaching them foreverafter to their ironic and bearded speaker: as it were; not to say; so to speak; memento mori; carpe diem; tempis fugit; carry coals to Newcastle; set the Thames alight; versatility is the hallmark of genius; fast nickels are better than slow dimes; non illigitimi carborundum; I’m not the bastard I seem to be; WELCOME TO COLLEGE. And that last bellowed phrase signaled welcome to new corners of poets, playwrights, novelists from the world’s wide four; and welcome to nutritious sites of historic and literary significance, narrated from Stineian memory; and to his home, and table, there to relish the easy, expert hospitality of his wife and family. And in my case, to England for the first time. Welcome to Dover, Mr. Stevick. I’ve got some things to show you.

At such a time as this, one wonders where to turn for language to help commemorate and reckon with his retirement. One tries to imagine a Gordon without him, and one remembers his important directives: Stevick, go to grad school; get your language requirement done; try radio; teach my oral interp class; apply for the position here; marry her, don’t wait too long; don’t wait too long—children are a blessing. These, too, Stine will say. How to gather the fruit of all that into words at once true and lovely? To quote usefully, “language staggers here”—or stumbles: at least mine does. Plus I’m afraid I’ll blub or do something ridiculous—

—because this spring I find myself toggling between “Stop all the clocks—Mark Stevick, are you grieving over Peter Stine soon leaving?” and what that means for us, for me in my 44th year to heaven—

—toggling between that and lines by Wordsworth, unveiled by Stine in his class:

Though nothing can bring back the hour

Of splendor in the grass, of glory in the flower,

We will grieve not, rather find

Strength in what remains behind;

In the primal sympathy

Which having been must ever be;

In the soothing thoughts that spring

Out of human suffering;

In the faith that looks through death,

In years that bring the philosophic mind.

Perhaps Peter is finding Wordsworth was right. Through God’s grace and Sue’s kidney, I trust he’ll continue to find strength in and among his loves: family, friends and students; reading, writing, performing (from these may there be no severing)—and, next summer, traveling back to England to lead a 10-day literary excursion. The aged eagle’s wings have plenty of spread left in them.

And though much is taken, much abides at Gordon after Stine. Innumerables. For starters, two essential courses in the English department, Nobel Prize winners and African Literature; a theatre major and a black box theatre with a plaque bearing his name; and most notably, row upon row of alumni, I among them, whose lives have borne out another of his sayings—that with a liberal arts degree, especially in English, you can think and write and speak well, so you can do anything.

Some would say, about a legacy like that, “Well done, good and faithful servant.”

What would Peter Stine say about it?

“Not bad.”

Here’s to my professor, colleague and friend, Peter W. Stine.

-Delivered at Peter Stine’s retirement dinner in 2008. He passed away August 5, 2011. We carry stones, and pile them on his.