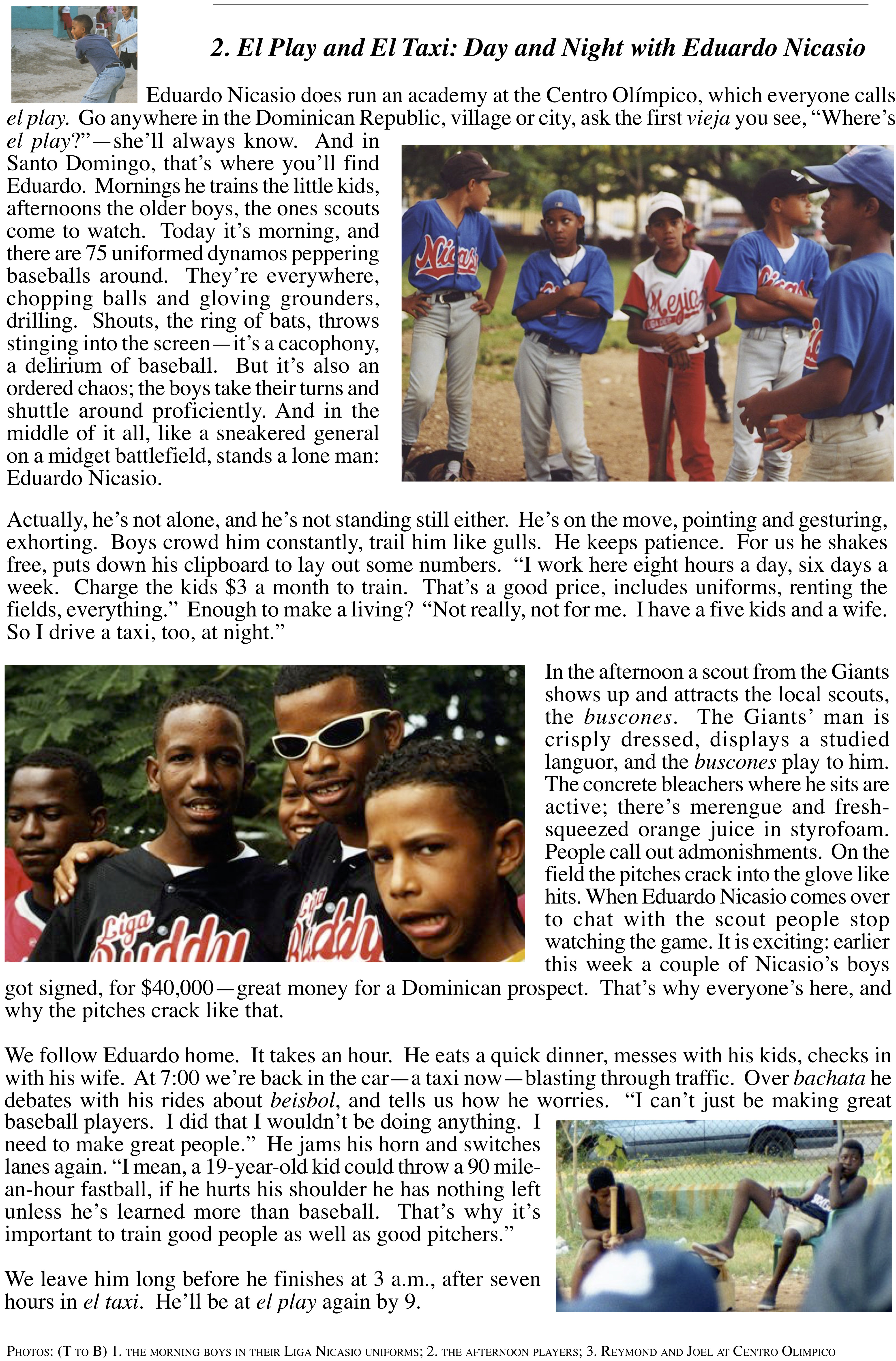

Andre Dubus III caught in our consciousness in 1999 or 2000. It was that novel of his, with the enviable title, House of Sand and Fog. Enviable, evocative.

We ourselves weren’t big into Oprah, who herself was big into his book (but I think that was after we’d already read it—we were ahead of the book clubs, just like Vadim Perelman, who tapped our guest for the rights to make it his first film, starring (why not admit?) one of our acting heroes, Sir Ben –

Kingsley).

But that was 2003, so let me sidle back to ’99 when we first turned over that savor-able title page.

What we remember is the Iranian colonel on the road crew, in the broad heat, with his trash bag and picker, his remote dignity under the squalid duress of his boss and sidecrew, unfolding his sack lunch of tea and radishes beneath a shade tree—Behrani, so courteous and unfathomable to the others…

This scene we remember rhyming with a work scene from another book: a kid/man digging trenches in the booming sun, Louisiana, his pick axe and shovel, and tough men with tougher hands, forgoing his lunch of sugar and lemons, sleeping it in the shade of a shed—his youthful prescience and resolve, so remarkable in his way…

—that scene written by Andre pére, father of our reader tonight, his book out the same year as his son’s, Meditations from a Movable Chair, 1999.

There must be a fire inside you to match the one outdoors, says the colonel-crewman.

I tasted a very small piece of despair, says the man/kid.

Twain scenes, of harsh senses and sensibility, of labor and lunchability, that make me wonder about this Dubus family craft – of writing: did the habit of art get handed down, passed along? It seems so. But how so? We may read about that in Townie, if we wish, which begins with another habit, too, the habit of pain, father and son running hilly, looping miles together, years before these two books I’ve mentioned.

—these books, son’s and father’s, that were passed along to me by our writer-saint, Lori Ambacher, fictionist, essayist, poet, friend of the Dubuses, too, who somehow ended up in Andre-father’s writers workshop. (If there was too much light in the room, it might have been Lori herself.) Lori who taught here at Gordon for twenty years, literature, conversating, creative writing. Lori whom we cherish and honor with this reading and this year’s Writers Series. Grove, Lori’s longtime partner, we’re especially glad to greet you tonight.

I think this introduction, now nearly at its end, has been more for Andre and me than for the rest of us here—I apologize for that.

But, really, how much introduction is needed? Nine books, three kids, one love-of-his-life, all jumbling around in a house in nearby Newbury that he built with hands hardened by #2 lead pencils.

Thank you, Mass Cultural Council; thank you, Lori Ambacher; and thank you, Andre—or as Lori called you—ladies and gentlemen, please join me in welcoming “Andre Three.”