Kwame Dawes keeps busy. He’s got irons in the fire.

Literal irons—?

No; you and he are good with metaphor: more on that anon.

Kwame is firing so many irons at any given time he might could be a farrier, fettling bright, battering sandals. Some examples of this:

-the Founder of Calabash International Literary Festival…seeking to transform the literary arts in the Caribbean by being the region’s best-managed producer of workshops, etc.—Kwame Dawes.

-the Founder of The African Poetry Book Fund…developing and publishing the poetic arts of Africa through programs and collaborations—Kwame Dawes.

-the editor of American Life in Poetry…finding and publishing poetry that speaks to various aspects of American existence—Kwame Dawes.

Maybe Kwame’s are actually clothing irons, the old-fashioned sad irons you’d heat in the fire—

Well, here, then, are some of those:

Kwame is editor of Prairie Schooner, AND founder of the South Carolina Poetry Initiative, AND creator of the project “Hope: Living and Loving with HIV in Jamaica,” AND poetry professor at two universities…

Goodness!—With all this, you won’t be surprised that Kwame was recently appointed the Patron Saint of Ironers-in-the-Fire—taking over for Leonardo de Vinci.

And, of course, he keeps writing poems.

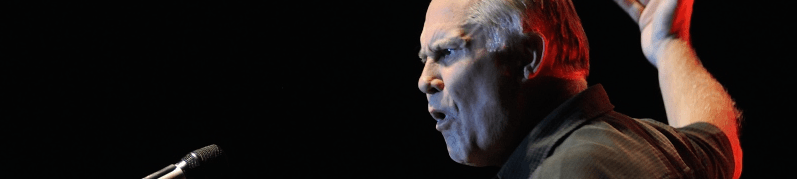

When you go online for poetry, you will likely see his face, a kind face, one whiche betokeneth his character.

This “irons in the fire”—isn’t really a metaphor, is it? More a figure of speech now, lifted from the common places of our lives, our lives full of particulars. “It is only,” he says, “in the mastering of the particular and the parochial that a sophisticated universalism can be achieved.” This masterful use of the particular is one of the things we admire about his poetry—

—what he does, for example, with pieces of scrubbed clothing hung out to dry, as in these last several couplets from “Ode to the Clothesline”

…taut lines, propped by poles

with nails for a hook, above

the startling green of grass and hedge,

the barefaced concrete steps,

the sky, inscrutable as a wall;

this is what one carries as a kind

of sweetness—the labor of brown hands

elbow-deep in suds, the rituals

of cleansing, the humility of a darning

or a frayed crotch, the dignity

of cleanliness, the democracy of truth,

the way we lived our lives in the open.

We savor the modest, apt description—of a startling green, a barefaced concrete, a sky inscrutable as a wall, and then that finish, where real laundry lifts into something universal and valuable.

This is uncoding landscapes (and histories and epiphanies) by things founded clean on their own shapes.

And this is one of the many pleasures and skills and marks of his work. I’ve read lots of it recently. Ilya Kaminsky, festival friend, says, “Why read Kwame Dawes? Because you cannot stop.” Exactly.

I know this too-long & too-brief intro has run a tad cheeky: It’s because I just can’t match the admiration I feel for him—his commitments, his rigor, his abundance, his joy-bringing. Even so, Kwame, I take heart from your remarking that “We are reverential by our noise and by our silence.” I bring you both.

Kwame Dawes is the author of novels, anthologies, nonfiction, and plays—along with 22 poetry collections—the most recent being Nebraska. Last summer he was named a finalist for the Neustadt International Prize for Literature.

Kwame, it is our great honor to have you address our festival today—in a craft talk entitled News from the Middle Way. Welcome, Kwame Dawes.